When I was a kid I used to do pratna in front of colour printed images of the Hindu devtas such as the small one above. This kind of religious iconography, which some call the “Hindu calendar art” has been the standard depiction of the Hindu pantheon for the past thirty or fourty years, at least. Shiva and Vishnu are usually painted with a blue skin, and the same applies for Vishnu’s avatars Rama and Krishna. I guess the reason for this odd colour ( which made me, as a child , wonder whether the Smurfs too had some religious/divine origin) comes from the fact that Rama and Krishna are described in the scriptures as being dark-skinned. However, Indians tend to take a dim view of the strong suntan, even with their gods, so that blue was settled upon as a compromise for their skin colour. People would usually justify it by quoting a line, I think from the Bhagavata Purana, which said that Krishna’s skin was of the colour of the dark blue lining of the monsoon clouds.

In Hindu calendar art, the gods usually have a round face, big round eyes, a sweet, benign appearance emphasised by their hand raised in blessing. Come to think of it, it was exactly the kind of depiction which would please a family doing pratna, and it fitted in well too with the wholesome atmosphere of Bollywood takes on the Ramayana or the Puranas, with Hanuman’s jolly bravado at the head of his cute monkey army, Sri Rama gently admonishing Sita (“ Parantu Sité….” ) and the motu kalu ( fat black) demons doing their booming demon laugh routine ( “bwaaaaa ha ha ha ha”).

But I couldn’t help noticing some pretty sharp nails which stuck out of this reassuring package. Shivji always struck me as having a rather odd appearance, with his cobra around his neck and the tiger skin wrapped around his loins, Tarzan-like. Then there was the goddess Durga , of severe beauty, martial and awe-inspiring, riding her roaring tiger. And I was disturbed and fascinated by the intense atmosphere during Cavadee, the Tamil festival – celebrated in February in Mauritius - in which the devotees of Muruga ( Shiva’s son) pierced themselves with needles and climbed a hill with a miniature temple on their shoulders.

And, talking about the Tamils, I couldn’t help being fascinated by the Tamil cinema’s take on Hindu mythology. Tamil religious films had a wild exuberance which I found mind boggingly exotic. They had little time for the gentle blandishments and staid demeanour of the religious movies of north India: down South, Parvati was fat and green-skinned, with her bosom almost bursting out of her tight striped nylon blouse, as showered her lord and husband Shiva ( wild-eyed, pot bellied, looking like a Mexican bandit with his handlebar moustache) with tirade after tirade of rolling Tamil, one hand on her plump hip, like a fisherwoman welcoming her man home from the bar. In one particularly spectacular incident, I saw the heavenly couple’s tiff ( I could make out, through the Tamil, that they were quarelling about who was the most powerful god between the two of them) escalate into regular battle, in the classical Indian religious movie style – arrows and tridents flying in the air, emitting rays and met in mid-air by counter arrows emitting couter rays – until at length, Shiva got so worked up that he sprang up a tongue of fire from within himself and throwing it at his wife, instantly burned her to ashes. I think she got reborn later into the movie.

The wild energy in those Tamil religious movies ! Parvati, after yet another quarrel with her hubby Shiva, creates by herself a boy, Ganesha. Her husband, coming back home after having gone to sulk on another mountain peak, is stopped dead on his tracks by the boy, who is standing as sentry to his mom. Shivji promptly lobs off the insolent kid’s head then, upon learning that that it is his son, sends his buddy Nandi the bull to fetch a replacement head. However, Nandi settles on cutting off the head of Indra’s favourite elephant Airavata ( Indra is the king of the lower gods in heaven). Indra’s heavenly army promptly comes to the rescue of the elephant and all hell breaks loose in heaven. Bing-bang-boom. Eventually Nandi gives a thrashing to Indra and slices off the elephant’s head, and Ganesha comes back to life. In another movie, little Muruga, the other son of Shiva, loudly berates his parents, accusing them of favouring his brother Ganesha, and then leaves the Himalaya for the land of the Tamils, where after a short 15 minute-long song of welcome by a Tamil saint, he promptly sets to work clearing the land of its goblins and demons. His dad Shivji sends the monster Veerabadra to give a helping hand. Bing-bang-smash.

These movies, with their intensely devotional songs in praise of furiously restless gods, gave me a hint of the no-holds barred religious imagination which was smouldering under the crust of mainstream Hindu respectability. Later on, I got to read translations of some of the major religious books ( the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, some of the Puranas) but also one or two anthologies giving extracts of older works such as the Vedas and some interesting, not too well known Puranas.

Although I had great respect for the higher summits of Hindu religious thought enshrined in the Vedantas and the Bhagavad Gita, I grew much more fascinated, over the years, by the dense forest of mythological lore whose dark foliage seemed to me to be whispering strange secrets; I liked to travel along its paths and see its strange, hidden beauties.

I was , and still am, specially interested by everything associated with Shiva and his spouse Parvati. My first impression, as a child, that Shiva was a pretty weird god came out to be true, and over the years I have made him my personal god ( ishta devata) precisely because he is an outsider, and that he is the very embodiment of ambiguity and contradictions. I soon came to realise that the crash-bang Shiva-and-Parvati stories so joyfully narrated by the Tamil movie industry were pretty tame stuff, compared to what the ancient texts had to say about the divine couple. They are litteraly out of this world.

Here, my keyboard fails me. I do not know how I can explain to the reader all the many, and contradictory aspects of the Shiva-Parvati couple without puzzling and boring him to death. At the esoteric level, Shiva is Conscience, an inert principle, the One Mind at the heart of the universe. Parvati is Shakti, Energy, the active principle which creates and destroys all things. The two of them together, Conscience and Energy, are fused in the state known as Sadashiva, which is the highest, most abstract level of Godhead. By separating, then fusing again at lower levels of creation, Shiva and Shakti create the universe, of which we know only a small part, given that our world is located between the higher lokas ( inhabited by divine creatures) and lower talas ( inhabited by infernal beings).

That’s for the abstract stuff, which goes into more profound levels than this ( philosophical Tantrism) about which I will not discuss, especially that I know only one or two things about it. Then there is the mythological level, which is so delightfully divine and human at the same time. We see Shiva and Parvati quarelling and making up like any couple. Here is an example of their tiffs ( Shiva, with characteristic male clumsiness, has made a joke about Parvati’s dark skin) :

Parvati: “Everyone blames someone else for his own deeds, and when anyone seeks something he is inevitably disappointed. I sought to win you, who wear a fragment of the moon, with shining acts of asceticism, and the reward for all my careful vow is that I am dishonoured at every step. I am not crooked, Sarva [ Shiva is “crooked” because he has three eyes] with the matted lock, nor am I irregular. You are patient enough with your own faults – and you are richly endowed with a veritable mine of faults (…) You called me “black” but you are known as the Great Black One. I will go to the mountain to leave my body by means of asceticism. There is no use in living just to be insulted by a rogue.

Shiva: “Truly the daughter is like her father in all ways [ Parvati is the daughter of the Himalaya mountain]. Your heart is as hard to fathom as a cavern of Himalaya,in which many sharp blades have accumulated, fallen from his cloud-garlanded peaks; your cruelty comes from his rock; your inconsistency from his various trees; your crookedness from his winding rivers; and you are as difficult to enjoy carnally as snow”

Parvati: “Sarva, do not blame virtuous people by comparing them with yourself, for all these faults have been transferred to you in the same way by your association with the wicked. You speak with many tongues because of your serpents; and you are devoid of affection because of your ashes. Your heart is defiled by the moon which is stained with a hare, and you get your stupidity from your bull. But what is the use of all this talk, which is merely tiresome to me ? You are frightening because you live in the burning ground, and you have no modesty, because you are naked. You are disgusting, because you carry a skull; who could bear you thus ?”

(from the Skanda Purana, quoted in Hindu Myths by Wendy Doniger)

She then leaves off in a huff, and the demon Adi decides to assume her shape so as to approach Shiva and kill him. In order to do so, Adi places sharp spikes inside her vagina. However, as she meekly approaches the Great God ( Shiva) and embraces him, the latter thinks: “Parvati is very proud and would not come back in such a manner” By closely observing her body, he realises it is not his wife. He then places a weapon on his penis and tears the demon apart. The real Parvati later comes back and the couple is reconciled.

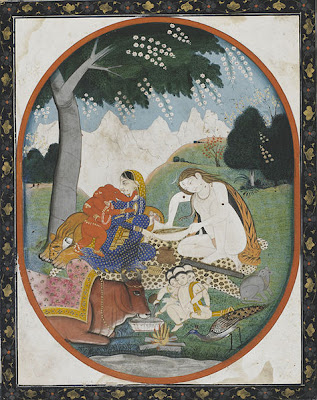

I love the depictions of the Shiva Parivar ( the family of Shiva) made by Indian miniature painters of the medieval period. I have seen only a few of them, but they capture with beautiful poetry and sense of humour all the contradictions inherent in the Shiva-Parvati couple. In the picture just above, we see the family settling for a meal. It seems that Shiva and Parvati are sifting something, maybe some cereal, through a white cloth. Ganesha, who is always closer to his mother, is bothering her a bit by climbing on her while she is at her task. Muruga is giving water to Nandi, Shiva’s vehicle and friend. Parvati’s vehicle, the lion is sleeping at her back. What strikes me as profoundly moving and funny in this picture is the whiteness of Shiva’s body, which stands in sharp contrast to the rest of the picture, which is quite colourful. This whiteness comes from the fact that Shiva always smears his body with the ash of the dead, a common ritual act for sadhus ( ascetics) in India. His strikingly white body, and his dreamy, detached expression underline the fact that he is an ascetic, which is in contradiction with his status as a householder.

To say that Shiva assembles all contradictions within himself, being beyond creation is one thing, but to see it represented in art, in this beautiful picture, is something else. I find it much superior to the modern “Hindu Calendar Art” such as the picture of Shiva at the beginning of my article. I guess most respectable Hindus try to “tame” Shiva and Parvati by representing them in a conventional manner, like in the picture above.

I can understand that most people would not be able to understand the value of the Shiva Parvati stories, they would be shocked by what they would see as strange stories about Shiva’s sperm, or about Kali making love to Shiva’s corpse, or again about Shiva dancing with his wife’s corpse on his shoulders. These stories are profound, fundamental poetic visions of the universe, but they are beyond most people’s understanding, nowadays. They are like strong alcoholic brews which would knock out most people dead.

As goes the saying : Who can understand Shiva ? The one who can do it, has become Shiva himself.

Ah well, anyway. I’ll indulge myself by quoting , to finish, a nice ( but very long) passage which I like quite a lot, which is the opening paragraph of the Mahanirvana Tantra ( the rest of the book is rather boring):

THE enchanting summit of the Lord of Mountains, resplendent with all its various jewels, clad with many a tree and many a creeper, melodious with the song of many a bird, scented with the fragrance of all the season’s flowers, most beautiful, fanned by soft, cool, and perfumed breezes, shadowed by the still shade of stately trees; where cool groves resound with the sweet-voiced songs of troops of Apsara, and in the forest depths flocks of kokila maddened with passion sing; where (Spring) Lord of the Seasons with his followers ever abide (the Lord of Mountains, Kailasa); peopled by (troops of) Siddha, Charana, Gandharva, and Ganapatya (1-5). It was there that Parvati, finding Shiva, Her gracious Lord, in mood serene, with obeisance bent low and for the benefit of all the worlds questioned Him, the Silent Deva, Lord of all things movable and immovable, the ever Beneficent and ever Blissful One, the nectar of Whose mercy abounds as a great ocean, Whose very essence is the Pure Sattva Guna, He Who is white as camphor and the Jasmine flower, the Omnipresent One, Whose raiment is space itself, Lord of the poor and the beloved Master of all yogi, Whose coiled and matted hair is wet with the spray of Ganga and (of Whose naked body) ashes are the adornment only; the passionless One, Whose neck is garlanded with snakes and skulls of men, the three-eyed One, Lord of the three worlds, with one hand wielding the trident and with the other bestowing blessings; easily appeased, Whose very substance is unconditioned Knowledge; the Bestower of eternal emancipation, the Ever-existent, Fearless, Changeless, Stainless, One without defect, the Benefactor of all, and the Deva of all Devas (5-10).

Shri Parvati said:

O Deva of the Devas, Lord of the world, Jewel of Mercy, my Husband, Thou art my Lord, on Whom I am ever dependent and to Whom I am ever obedient. Nor can I say ought without Thy word. If Thou hast affection for me, I crave to lay before Thee that which passeth in my mind. Who else but Thee, O Great Lord, in the three worlds is able to solve these doubts of mine, Thou Who knowest all and all the Scriptures (11-13).

Shri Sadashiva said:

What is that Thou sayest, O Thou Great Wise One and Beloved of My heart, I will tell Thee anything, be it ever so bound in mystery, even that which should not be spoken of before Ganesha and Skanda Commander of the Hosts of Heaven. What is there in all the three worlds which should be concealed from Thee? For Thou, O Devi, art My very Self. There is no difference between Me and Thee. Thou too art omnipresent. What is it then that Thou knowest not that Thou questionest like unto one who knoweth nothing (14-16).

The pure Parvati, gladdened at hearing the words of the Deva, bending low made obeisance and thus questioned Shangkara.

Shri Adya said:

O Bhagavan! Lord of all, Greatest among those who are versed in Dharmma, Thou in former ages in Thy mercy didst through Brahma reveal the four Vedas which are the propagators of all dharmma and which ordain the rules of life for all the varying castes of men and for the different stages of their lives (18-19). In the First Age, men by the practice of yaga and yajna prescribed by Thee were virtuous and pleasing to Devas and Pitris (20). By the study of the Vedas, dhyana and tapas, and the conquest of the senses, by acts of mercy and charity men were of exceeding power and courage, strength and vigour, adherents of the true Dharmma, wise and truthful and of firm resolve, and, mortals though they were, they were yet like Devas and went to the abode of the Devas (21, 22). Kings then were faithful to their engagements and were ever concerned with the protection of their people, upon whose wives they were wont to look as if upon their mothers, and whose children they regarded as their very own (23). The people, too, did then look upon a neighbour’s property as if it were mere lumps of clay, and, with devotion to their Dharmma, kept to the path of righteousness (24). There were then no liars, none who were selfish, thievish, malicious, foolish, none who were evil-minded, envious, wrathful, gluttonous, or lustful, but all were good of heart and of ever blissful mind. Land then yielded in plenty all kinds of grain, clouds showered seasonable rains, cows gave abundant milk, and trees were weighted with fruits (25-27). No untimely death there was, nor famine nor sickness. Men were ever cheerful, prosperous, and healthy, and endowed with all qualities of beauty and brilliance. Women were chaste and devoted to their husbands. Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras kept to and followed the customs, Dharmma, yajna, of their respective castes, and attained the final liberation (28-29).

After the Krita Age had passed away Thou didst in the Treta Age perceive Dharmma to be in disorder, and that men were no longer able by Vedic rites to accomplish their desires. For men, through their anxiety and perplexity, were unable to perform these rites in which much trouble had to be overcome, and for which much preparation had to be made. In constant distress of mind they were neither able to perform nor yet were willing to abandon the rites.

Having observed this, Thou didst make known on earth the Scripture in the form of Smriti, which explains the meaning of the Vedas, and thus delivered from sin, which is cause of all pain, sorrow, and sickness, men too feeble for the practice of tapas and the study of the Vedas. For men in this terrible ocean of the world, who is there but Thee to be their Cherisher, Protector, Saviour, their fatherly Benefactor, and Lord? (30-33).

Then, in the Dvapara Age when men abandoned the good works prescribed in the Smritis, and were deprived of one half of Dharmma and were afflicted by ills of mind and body, they were yet again saved by Thee, through the instructions of the Sanghita and other religious lore (34-36).

Now the sinful Kali Age is upon them, when Dharmma is destroyed, an Age full of evil customs and deceit. Men pursue evil ways. The Vedas have lost their power, the Smritis are forgotten, and many of the Puranas, which contain stories of the past, and show the many ways (which lead to liberation), will, O Lord! be destroyed. Men will become averse from religious rites, without restraint, maddened with pride, ever given over to sinful acts, lustful, gluttonous, cruel. heartless, harsh of speech, deceitful, short-lived, poverty-stricken, harassed by sickness and sorrow, ugly, feeble, low, stupid, mean, and addicted to mean habits, companions of the base, thievish, calumnious, malicious, quarrelsome, depraved, cowards, and ever-ailing, devoid of all sense of shame and sin and of fear to seduce the wives of others. Vipras will live like the Shudras, and whilst neglecting their own Sandhya will yet officiate at the sacrifices of the low. They will be greedy, given over to wicked and sinful acts, liars, insolent, ignorant, deceitful, mere hangers-on of others, the sellers of their daughters, degraded, averse to all tapas and vrata. They will be heretics, impostors, and think themselves wise. They will be without faith or devotion, and will do japa and puja with no other end than to dupe the people. They will eat unclean food and follow evil customs, they will serve and eat the food of the Shudras and lust after low women, and will be wicked and ready to barter for money even their own wives to the low. In short, the only sign that they are Brahmanas will be the thread they wear. Observing no rule in eating or drinking or in other matters, scoffing at the Dharmma Scriptures, no thought of pious speech ever so much as entering their minds, they will be but bent upon the injury of the good (37-50).

By Thee also have been composed for the good and liberation of men the Tantras, a mass of Agamas and Nigamas, which bestow both enjoyment and liberation, containing Mantras and Yantras and rules as to the sadhana of both Devis and Devas. By Thee, too, have been described many forms of Nyasa, such as those called srishti, sthiti (and sanghara). By Thee, again, have been described the various seated positions (of yoga), such as that of the "tied" and "loosened" lotus, the Pashu, Vira, and Divya classes of men, as also the Devata, who gives success in the use of each of the mantras (50-52). And yet again it is Thou Who hast made known in a thousand ways rites relating to the worship with woman, and the rites which are done with the use of skulls, a corpse, or when seated on a funeral pyre (53). By Thee, too, have been forbidden both pashu-bhava and divya-bhava. If in this Age the pashu-bhava cannot exist, how can there be divya-bhava? (54). For the pashu must with his own hand collect leaves, flowers, fruits, and water, and should not look at a Shudra or even think of a woman (55). On the other hand, the Divya is all but a Deva, ever pure of heart, and to whom all opposites are alike, free from attachment to worldly things, the same to all creatures and forgiving (56). How can men with the taint of this Age upon them, who are ever of restless mind, prone to sleep and sloth, attain to purity of disposition? (57). By Thee, too, have been spoken the rites of Vira-sadhana, relating to the Pancha-tattva – namely, wine, meat, fish, parched grain, and sexual union of man and woman (58-59). But since the men of the Kali Age are full of greed, lust, gluttony, they will on that account neglect sidhana and will fall into sin, and having drunk much wine for the sake of the pleasure of the senses, will become mad with intoxication, and bereft of all notion of right and wrong (61). Some will violate the wives of others, others will become rogues, and some, in the indiscriminating rage of lust, will go (whoever she be) with any woman (62). Over eating and drinking will disease many and deprive them of strength and sense. Disordered by madness, they will meet death, falling into lakes, pits, or in impenetrable forests, or from hills or house-tops (63-64). While some will be as mute as corpses, others will be for ever on the chatter, and yet others will quarrel with their kinsmen and elders. They will be evil-doers, cruel, and the destroyers of Dharmma (65-66). I fear, O Lord! that even that which Thou hast ordained for the good of men will through them turn out for evil (67). O Lord of the World! who will practise Yoga or Nyasa, who will sing the hymns and draw the Yantra and make Purashcharana? (68). Under the influences of the Kali Age man will of his nature become indeed wicked and bound to all manner of sin (69). Say, O Lord of all the distressed! in Thy mercy how without great pains men may obtain longevity, health, and energy, increase of strength and courage, learning, intelligence, and happiness; and how they may become great in strength and valour, pure of heart, obedient to parents, not seeking the love of others’ wives, but devoted to their own, mindful of the good of their neighbour, reverent to the Devas and to their gurus, cherishers of their children and kinsmen (70-72), possessing the knowledge of the Brahman, learned in the lore of, and ever meditating on, the Brahman. Say, O Lord! for the good of the world, what men should or should not do according to their different castes and stages of life. For who but Thee is their Protector in all the three worlds?

( from the translation by Arthur Avalon)

No comments:

Post a Comment